Charles Bradford and James Johnson were just looking for bait. The Murfreesboro boys were fishing in the Caney Fork River in the early 1880s when, on opening one of the mussels they had pulled from the mouth of Indian Creek, they found a large white pearl. They took it to William Wendel, a local druggist, who sent it off to Tiffany’s in New York. A few days later the boys had a check for a then-impressive $83.

Charles Bradford and James Johnson were just looking for bait. The Murfreesboro boys were fishing in the Caney Fork River in the early 1880s when, on opening one of the mussels they had pulled from the mouth of Indian Creek, they found a large white pearl. They took it to William Wendel, a local druggist, who sent it off to Tiffany’s in New York. A few days later the boys had a check for a then-impressive $83.

More than 100 years later, through boom and bust, and despite pollution, over-harvesting, TVA dams and the vicissitudes of fashion, mussels are bringing up to $40 million a year into Tennessee, and the freshwater pearl has been, since 1979, the official state gem. The kind of serendipity experienced by Charles and James had happened before in Tennessee, and it would happen again. A few years earlier, near Lancaster, a fisherman found a pearl that eventually sold for $2,000 in New York. Later, a farmer idly picking up a mussel while his horse drank was paid $190 for the pearl inside.

In each case, what followed was a rush to get in on the action, with many people from all walks of life spending their spare time in nearby rivers and creeks. They would dig the mollusks by hand, or with forks or spades, split them with knives, and discard those that were pearl-less – the overwhelming majority of them. Before long, the shallows had been stripped of mussels in many places, and people were using dredging and other methods to take them from deeper water.

The process increased even more dramatically with the use of the mother-of-pearl from these shells in the manufacture of buttons. Not long after the turn of the century, the rate of depletion was concerning a number of people. W. E. Myer of Carthage, speaking before the Tennessee Academy of Science in 1914, decried “the heedless total working out and total destruction of every mussel in each mussel bed and leaving no mussels to reproduce the race.”

Despite his protestation, Myer, whose brother was a major New York pearl dealer, was one of many (explorer Hernando de Soto had been the first) to dig up the graves of Native American mound builders looking for the popular gem. Prehistoric residents had long been avid consumers of the mussels, both for food and for adornment, and archaeological excavations have often turned up large heaps of shells. Since pearls are a rare commodity, the selling of natural pearls would long be a minor sideline to the shell business, and once plastics replaced shell buttons on a large scale, it would take a new industry from the Far East to spark Tennessee’s modern mussel business.

Pearls are formed when mollusks – clams, oysters, or mussels – secrete layer after layer of ultra-thin nacre in an onion-like manner around an irritant, usually a tiny parasite or piece of shell. Waiting for nature to conduct that cycle is, of course, an exasperating business for those trying to make a living selling pearls, but it wasn’t until the turn of the century that an effective process for “culturing,” or manufacturing, pearls, was developed.

Pearls are formed when mollusks – clams, oysters, or mussels – secrete layer after layer of ultra-thin nacre in an onion-like manner around an irritant, usually a tiny parasite or piece of shell. Waiting for nature to conduct that cycle is, of course, an exasperating business for those trying to make a living selling pearls, but it wasn’t until the turn of the century that an effective process for “culturing,” or manufacturing, pearls, was developed.

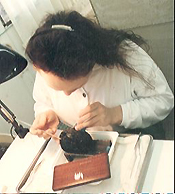

Two men working independently in Japan determined that secretions from the mantle – the tissue which lines the shell – create mother-of-pearl, from which the pearls themselves are made. Both men inserted tiny nuclei that mimicked the natural irritants and added a small piece of mantle particle from another mussel as well, successfully spurring pearl production.

A third man, flamboyant entrepreneur Kokichi Mikimoto, received a Japanese patent for the first cultured round pearl in 1908 and took his case for the gem to the large American market, displaying creations like a pearl Statue of Liberty (nacre can be built up around a wide variety of shapes). As natural pearls became more scarce, cultured pearls took an ever-larger share of the market, dominating it almost completely by 1960.

The Japanese, who carefully guarded their production secrets, long dominated world markets. In the manufacturing process, though, they found themselves tied to Tennessee mussels. The Japanese make small pellets from shells and insert them as the starter irritants, and Tennessee’s waters produce some of the best shells for the process, since they’re less likely to be rejected and they produce more uniform pearls. In fact, some 40% of the shells used by the Japanese come from Tennessee companies.

There are over 70 species of mussels in Tennessee’s waters, down from 127 a century ago. Nearly two dozen of those remaining are endangered or threatened, mostly because of pollution and TVA dams, which rob rivers of the swift water many of the mollusks rely on for feeding. There are a dozen species, which can be removed from the riverbed, and four make up virtually all of those sold commercially-the mapleleaf, three-ridge, ebony and washboard mussels.

There are over 70 species of mussels in Tennessee’s waters, down from 127 a century ago. Nearly two dozen of those remaining are endangered or threatened, mostly because of pollution and TVA dams, which rob rivers of the swift water many of the mollusks rely on for feeding. There are a dozen species, which can be removed from the riverbed, and four make up virtually all of those sold commercially-the mapleleaf, three-ridge, ebony and washboard mussels.

There are still two ways of taking mussels – by hand and by brail, a sort of underwater rake towed by a boat. Since most commercially viable beds are in deep water, divers do the bulk of the hand harvesting. Often working with partners who keep an eye on air pumps in boats above, divers descend deep into waterways like Kentucky Lake, collecting sacks-ful of shells.

It’s dangerous work conducted in low-visibility conditions, often by untrained divers, and there were eight deaths in 1990 among the 2,300 divers in Tennessee’s waters. That figure, though, was abnormally high, according to Robert Todd, a commercial fishing/musseling coordinator with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, who says one or two deaths a year is a more common number.

The shells are taken to dealers, with Tennessee Shell Co. being the largest. The company pays from 55 cents to $4.35 a pound, depending on the size and species of shell, and a good diver can make well over $200 a day. Shells are sorted, sacked, and shipped by truck to Memphis, where they are taken by rail to the West Coast and then by ship to Japan.

TWRA estimated the statewide harvest of shells at 4,760 tons in 1990. It considered that figure too high to be sustainable, and introduced new size limits and other regulations that cut the 1991 harvest to about 2,400 tons. Related and peripheral industries make the mussel business a $20 million per year industry.

One of its key players is John Latendresse, who owns American Pearl Co., which designs and manufactures jewelry, selling to a clientele that includes Service Merchandise and Macy’s. He also owns American Pearl Farms, the nation’s only successful pearl culturing operation, developed after years of painstaking work. (The pearl farm is located at Birdsong Resort & Marina in Camden.) Latendresse will harvest pearls from 500,000 shells this year.

One of its key players is John Latendresse, who owns American Pearl Co., which designs and manufactures jewelry, selling to a clientele that includes Service Merchandise and Macy’s. He also owns American Pearl Farms, the nation’s only successful pearl culturing operation, developed after years of painstaking work. (The pearl farm is located at Birdsong Resort & Marina in Camden.) Latendresse will harvest pearls from 500,000 shells this year.

The companies are headquartered in Camden, where Latendresse, who also has the world’s largest collection of freshwater pearls, has done business since 1954. Despite the classic success of all aspects of Tennessee’s freshwater pearl business, daunting problems remain. Pollution, particularly from farm chemicals, has been a major problem on Kentucky Lake for years, and Latendresse lost hundreds of thousands of dollars when a portion of his mussel crop was wiped out in 1989.

In many sections of the state only a small percentage of the mussels found by divers are for sale. Even the colder-than-normal winter of 1994 had effect, delaying mussel harvesting and damaging a portion Latendresse’s physical plant. TWRA’s Todd sees progress in the implementation of size limits and other measures, though. “I think we have protected the mussels to assure they at least attain a size at which they’re capable of sexual reproduction,” he said. “There is a lot of pressure on the resource our best guess is that about 80 percent of what attains legal size in one year is removed. We’re managing on the edge there, but we feel we’ve got the size limits large enough that our resource will be protected.”

The agency has imposed sanctuaries in areas that contain rare mussels and, while poaching remains a problem, a fee charged buyers of shells has enabled TWRA to hire a mussel enforcement officer as well as a biologist and technician. It remains to be seen whether those efforts can turn the tide in the effort to improve conditions for our most fragile state symbol, one extremely sensitive to the kinds of problems growth and pollution bring.

(Reprinted from Tennessee State Symbols, Rob Simbeck, 1995)

Request a free

Request a free